Part 5: Golden Banners

Chapter 5 – Unfurling the Golden Banner – 1123 to 1144The world of twelfth century is a fast changing one.

After being defeated yet again by the Byzantine Empire, the Fatimid Caliphate collapsed into sectarian infighting and civil war, with Sunni lords throughout the Levant and Hejaz throwing off the yoke of the Fatimids and seizing their independence.

In Europe, four consecutive Italian Holy Roman Emperors has marked the transition of power from Germany to the Italian peninsula, allowing the distant Norwegians to break away in an uprising. The dominance of the Empire is quickly beginning to slip, with France fast recovering from its defeat and a new power on the rise in the East.

On the Iberian peninsula, meanwhile, the two fast-growing powers of Aragon and the Aftasids are on a collision course, with war between the two rivals quickly becoming inevitable.

In the Sheikhdom of Cádiz, however, the most pressing concern in the recent transition of power. The tyrannical Sheikh Az’ar, aptly nicknamed the ‘Son of Iblis’, has died under suspicious circumstances, and the newly-formed Regency Council is quick to restore order by naming his nephew as his heir and successor.

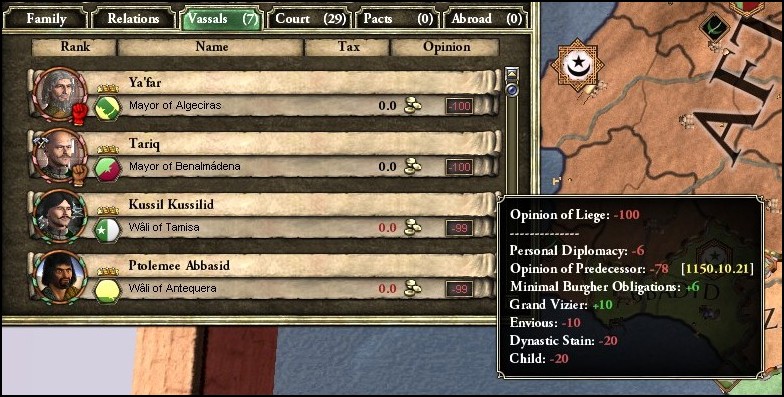

That won’t be enough to calm the wazirs and walis of the Sheikhdom, however, with many still bitter over Azar’s treatment of their families, their estates and their noble rights.

To try and shore up some support, the Regency Council agree to the demands of the Court Imam and leave the rearing of young Masud to the clergy, who were determined to avoid another disaster like Az’ar.

As unrest bubbles in Cádiz, however, outright conflict has finally erupted between the Aftasid Sultanate and the Kingdom of Aragorn. A new sultan had risen to rule the Muslim kingdom, with the young Sultan Lubb declaring his intention to seize all of Granada from the Christians, calling on all Muslims to join him under the banner of Allah.

The recently-crowned King Manrique of Aragorn was no stranger to war, however, and he had been preparing for the eventual Aftasid invasion for years now. Upon the declaration of war, Manrique ordered his prepared forces to quickly cross the border and put the strategic city of Cordoba under siege, and with Aftasid forces slow to respond, he managed to breach and sack the city within weeks.

Sultan Lubb didn't retaliate for months, but in the height of the blistering summer of 1124, he finally attacked King Manrique with almost 12000 men - only to be crushed in the ensuing battle. With thousands dead and his army destroyed, Sultan Lubb was forced to sue for peace, which Manrique granted under humiliating terms.

The Andalusi Muslims seem to have lost the favour of Allah, because this disastrous loss was quickly followed by the scourge that is typhus. Without the resources to combat plague, Camp Fever rapidly spread through southern Iberia, sending tens of thousands of peasants to pox-ridden graves in a matter of weeks.

Sultan Lubb, who was looking for some way to regain the influence and prestige lost in his war with Aragon, chose this moment to pounce. Under the guise of ‘security against the Christians’, the Aftasid army stormed into Jizrunid territories with the intention of conquering Malaga, outraging many of the nearby taifas.

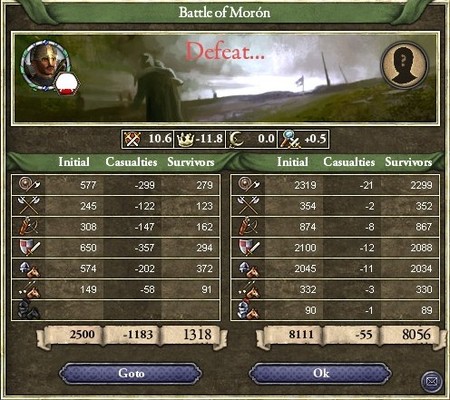

The Regency Council, who had not expected a war against their Muslim brethren, were slow to respond. Eventually, after taking out several loans from the Jewish communities, a mercenary army numbering 2500 was thrown together and sent to halt the advance of the Aftasids.

Stopping the advance of 8000 men is easier said than done, however.

With that, the humiliated Regency Council were forced to acquiesce to Aftasid demands, and the rich city of Malaga was lost.

It was in the midst of this war that the young Sheikh Masud finally came of age, and was confirmed as ruler of Cádiz, Algeciras

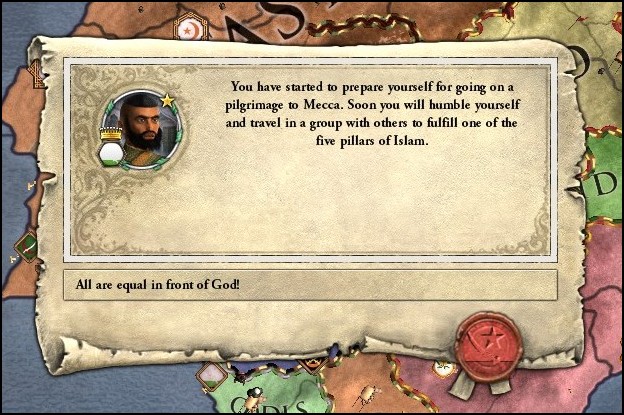

Not long after coming into his majority, and at the behest of the clergy, the new Sheikh decided to go on Hajj before assuming his political responsibilities. He set off from Cádiz early in 1137, and though he would be gone for no longer than a few months, Masud came back a changed man.

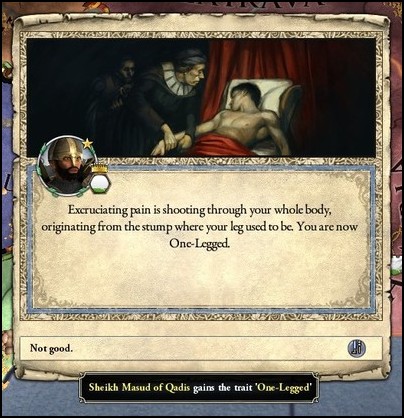

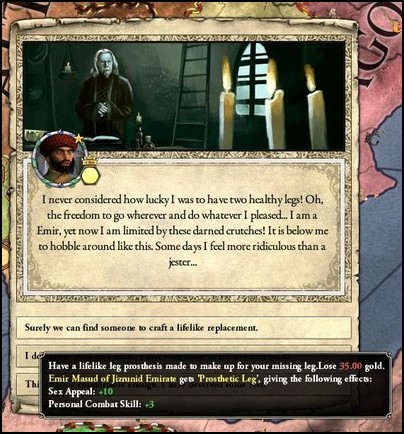

More specifically, on the route back from Mecca, Masud’s caravan party fell under attack by a band of brigands. They were eventually repulsed, but during the bloody struggle, the young Sheikh was dealt a tremendous blow from which he would never recover.

This, upon Masud’s return to Cádiz, quickly brought to memory the crippling injury that his uncle Az’ar had suffered, along with the miraculous recovery shortly thereafter. Sheikh Masud himself had never believed these fantastical rumours, and refused to lower himself to the level of court gossip by entertaining such thoughts.

He knew that he would have to find a way to walk without crutches, however - a cripple could not lead men into battle. So he employed the talents of his court physicians, who moulded him a prosthetic leg out of iron, with adjustable harnesses and sockets. His movement was still heavily restricted, but with it, Masud would be able to walk without crutches, he would be able to hold a sword and shield, and he would be able to guide a horse. That was enough for him.

With that, Masud could finally begin focusing on state emergencies, of which there were many. Firstly, hoping to ward off another Aftasid attack, Masud decided to approach the Almoravid Sultanate in the hopes of forming an alliance. After a few weeks of negotiation, and a match between Masud’s aunt and the Moroccan king, Sultan Umar finally agreed to come to the aid of Cádiz in war.

And war was certainly coming, Masud had no doubts about that. If Cádiz was to survive the onslaught of Aftasids and Christians, then it would have to expand soon, before all of Iberia was carved between the two great powers.

But to do that, the Sheikh knew he had to have the clergy on his side, they had proven an insurmountable foe to his predecessor. So at every given opportunity, Masud tried to solidify his relations with the Court Imam, donating large sums of money in sadaqah, building several mosques and madrasahs through Cádiz, and even giving the ulema full authority on all religious matters within the Sheikhdom.

Eventually, his efforts paid off and Sheikh Masud was able to convince his vassals to contribute more troops to the Cádizian army, a feat which Az’ar had never been able to achieve.

Shorty thereafter, Masud began implementing the new laws and expanding his army, financing the construction of barracks and militia grounds throughout Cádiz to aid in the recruitment and training of youths.

Before his plans could come into full fruition, however, a golden opportunity arrived. Early in 1140, the small but powerful Abbadid Emirate declared war on the Kingdom of Aragon, sending 7000 men to siege and occupy the Baleares.

Pretty much everyone, Masud included, expected Aragon to easily crush the Abbadids in battle, as they had done the Aftasids. After launching a naval invasion into Mallorca with 14000 troops, however, King Manrique suffered a devastating defeat and lost more than 4000 men, with the smaller Abbadid force emerging victorious.

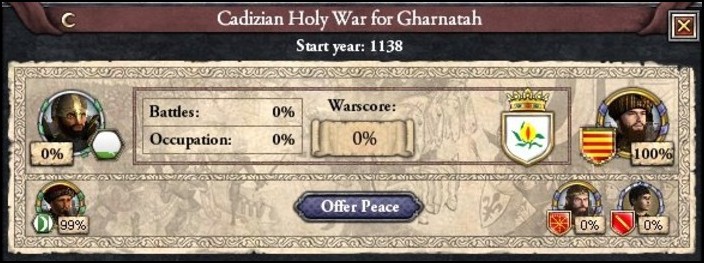

This was an opportunity Sheikh Masud didn’t dare pass on. So, after briefly consulting his council, the Sheikh raised his small army and declared war on the vast Kingdom of Aragon, citing his divine favour in a sermon to his vassals.

Divine favour was all well and good, but it was men and steel that won battles, so after his speech Masud sent envoys to his allies in Morocco. Sultan Umar was quick to reply, eager to bloody his Mediterranean rivals, and raised his own considerable armies in solidarity with Cádiz.

King Manrique had allies of his own, however, and the Christian principalities banded together in opposition of Muslim aggression. Both the Duchy of Toledo and the Kingdom of Navarra rushed to join Aragon in yet another clash of Islam and Christendom.

After delaying his first incursion for a few weeks, to give the Almoravids time to join up with him, Sheikh Masud began the invasion into Aragon early in 1141.

The 12000-strong Muslim force lay siege to Granada, but the castle was powerful and well-defended, the Jimena Kings had spared no expense in fortifying their borders. After a few weeks of surrounding the city, however, the defenders gradually began starving and turning on each other. Eventually, one of the guardsmen was bribed into leaving a side-door ajar, and Sheikh Masud conducted a night raid to seize the tower, before opening the gates to the rest of his army.

The short skirmish that followed was thick and bloody, with many Christian faithful laying down their lives rather than surrender, and Masud had to wade through streets of blood before the citadel finally capitulated. The day ended with a crushing Muslim victory, however, and any dissent was suppressed shortly after.

With Granada firmly under his control, Sheikh Masud then led the combined Jizrunid-Almoravid force further north, putting the fortress of Almeria under siege. Much more lightly defended, it didn’t take long to scale the walls and put the garrison to the sword, and the rest of the castle quickly followed.

Whilst they were busy sacking Almeria, however, a Toledo-Aragonese army led by King Manrique himself managed to circle around the Muslims and assault Granada, quickly taking the castle and executing its occupiers. With Granada retaken, Manrique led his army to meet the Muslims in battle, hoping to fully expel the invaders in a decisive pitched battle.

Sheikh Masud was able to fortify Almeria just before their arrival, however, and the dug-in Cádizian-Moroccan army easily repulsed the Christians, slaughtering them by the thousand.

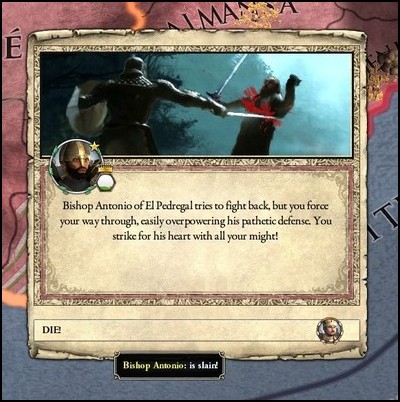

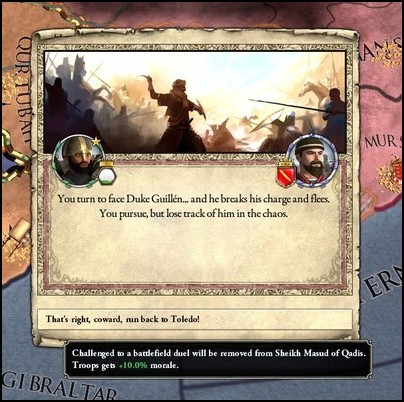

Masud actually managed to distinguish himself well during the battle, his prestige rocketing as stories spread about how the Sheikh viciously cut down a warrior-bishop in the thick of the battle, about how he led a heroic charge that broke the enemy line, about how he inspired such terror that even the Dukes and commanders of the opposing army faltered, before fleeing the field. All this, despite his peg leg and hobbled gait.

With the Toledo-Aragonese force utterly crushed, Sheikh Masud led his army south and recaptured Granada, which surrendered after only a token defense.

And with that, King Manrique had no choice but to kneel, what with his army in tatters and half his kingdom under occupation. The negotiations were short and bitter, with Masud demanding Granada and its immediate environs, along with yearly tribute and a humiliating acknowledgment of Aragonese defeat.

And when Masud returned to Cádiz, the sins and crimes of his uncle seemed forgotten, with the vibrant young sheikh inspiring the imagination of the peasantry and nobility alike, uniting them behind him in a way thought impossible a few short months past. With his victory on the lips of every man, woman and child, Masud took the opportunity to declare himself "Emir of Qadis", a proclamation that was quickly recognised by his vassals and neighbours.

Scars are not so easily forgotten, and Masud's ambition is sure to ruffle some feathers, especially amongst the Aftasids. The young emir isn’t foolish enough to believe that his conflicts are at end, and as the spirited fervour following his victory begins to die down, he turns his attention to lost titles and religious betrayal: Malaga.